Veteran’s quick reactions saved lives during Las Vegas shooting

The courtyard pulsed with the excitement of a three-day weekend.

Students scuffled about, grabbing items from lockers and stuffing them into book bags, smiles spreading across faces.

As they spilled out the front entrance of the elementary school, the buses, lined up in an orderly fashion, waited for them.

“Thanks for sticking up for me today, Mr. Donohue,” one child shouted over the end-of-the-day melee, sharing a look of camaraderie with his new friend.

The students are learning how to be upstanders, the principal said, people who stand up and speak out against bullies.

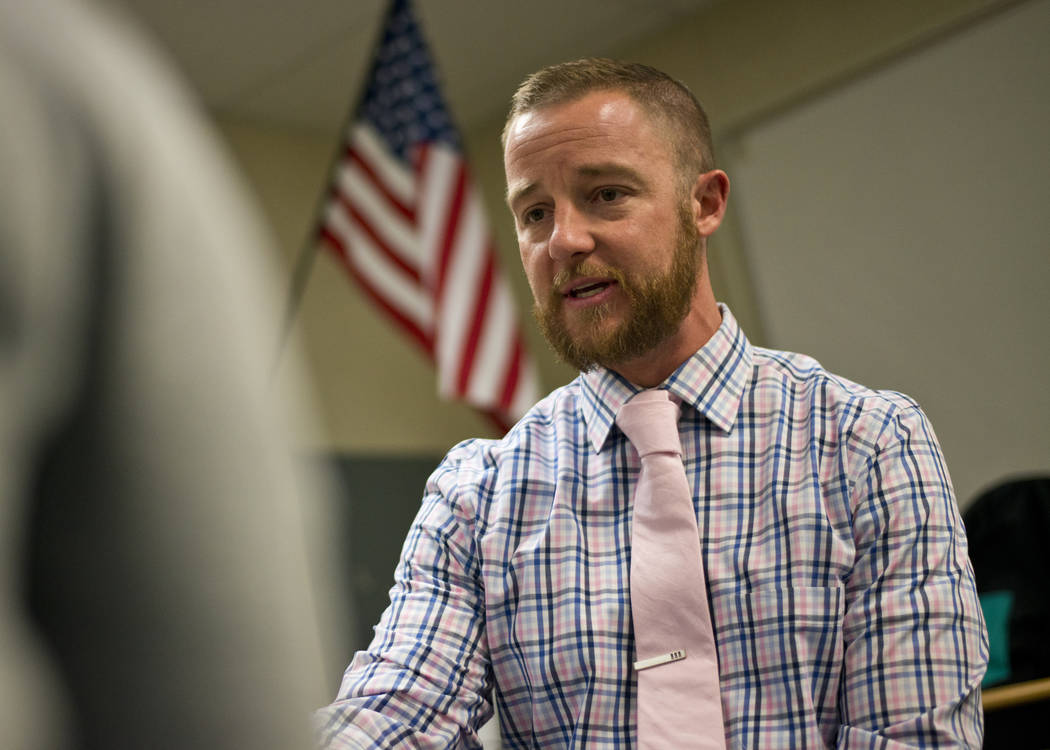

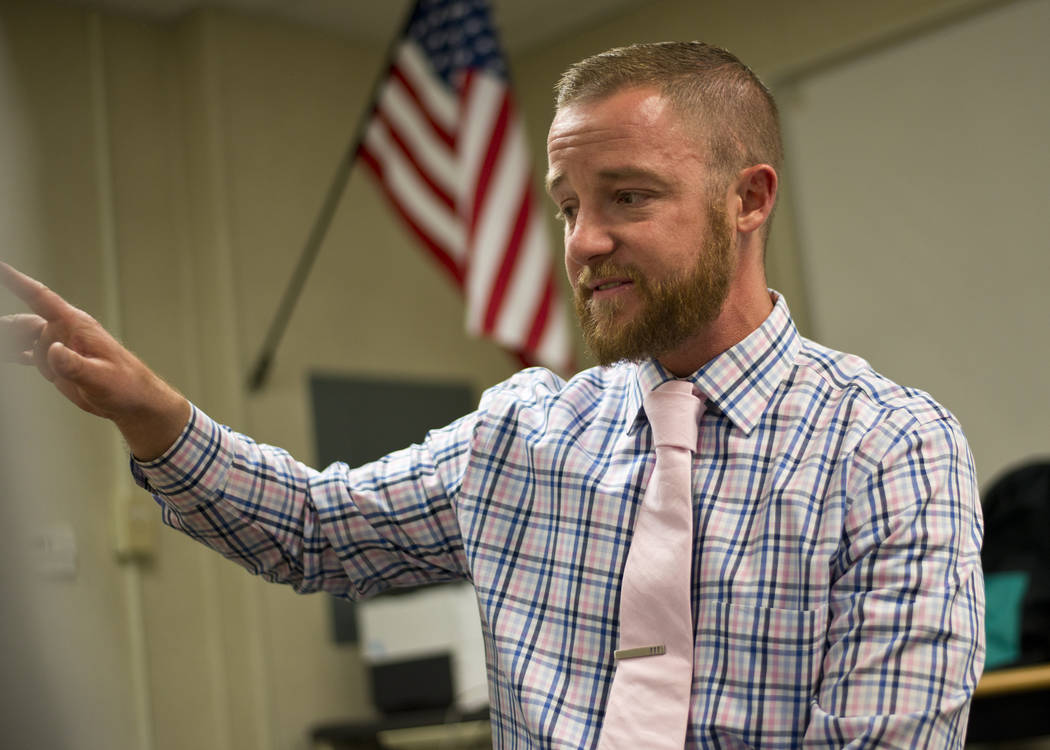

And what better example than Colin Donohue?

The first barrage

Donohue, 35, rejoined the Clark County School District as a literacy specialist last week — two months after returning home from a nine-month tour of duty in Iraq.

He was only three weeks removed from his time overseas when the Route 91 Harvest festival turned into an active war zone.

“For me, I’ve heard gunfire before,” Donohue said. “I heard it in Iraq. And I was like there’s no way. There’s no way this is gunfire. You hear the first barrage, and the first barrage goes for a while. And then you start hearing people scream.”

This was the Army captain’s third year at the music festival. Prior to the gunfire, he was having an awesome time with his friends, who were staying in Room 31305 of the Mandalay Bay.

And while he loves all kinds of country music, and enjoyed myriad bands over the three-day festival, he was there for the final act, just like everybody else.

“Then you see Jason Aldean run across the stage,” Donohue said. “I said ‘it’s gonna be alright, we’re going to be good,’ and I turn around and people were starting to get low, they’re all starting to get low. The guy to my left … dropped.”

He was shot in the leg. The gunfire became real in that moment.

“I told him you need to put your finger in it, hold your legs together, keep pressure on it,” Donohue said.

The call

The Las Vegas native joined the Army Reserves on Dec. 9, 2009 when he was six credits from finishing his master’s degree.

He said he thought it was always something he wanted to do, and something he could learn from. Both of his grandfathers were lieutenant colonels in the Air Force.

About two years after joining, Donohue was part of a search and extraction team, and received training on how to respond in mass casualty events, such as an earthquake.

“In a majority of scenarios, the event already occurred,” Donohue said. “You’re not part of this scenario. You are the call — ‘Hey, we need your help,’ and we show up.”

Not on Oct. 1.

After tending to the man with the injured leg, Donohue turned his attention to his two friends, Belinda and Olivia.

“That was pretty much the only thing I worried about,” he said.

He led them across the field to the VIP section that had a set of bleachers. He ordered them to stay there, and bolted in the opposite direction, even as the second barrage of gunfire was erupting.

“I ran to the furthest person I saw that nobody was with,” he said. “I turned around, and trauma nurse — Olivia — is in my hip pocket.”

They started working on each person, going clockwise from the beginning of the stage.

“There were between eight and 12 that were just dead, right in a row, all gone,” Donohue recalled. “Head shot, chest shot, head shot.”

Donohue was trying to find entry and exit wounds for the victims, the majority of whom were dead, and asked all of the other helpers — nurses, doctors — what he could do to help.

“People were arguing on what to do and how to do it, but at the same time, we came together,” he said.

At one point he ripped out a red gate, ignoring the pain that came with it, to create a makeshift gurney. In another moment, he came across a girl who was in shock, and told someone nearby to get her out of the venue.

He doesn’t remember when the bullets ended their descent on the crowd, but knows he was one of the last people to leave the venue.

Iraq status

Work has been a welcome relief to Donohue.

He’s back in a routine, something he got away from upon returning home from Iraq, and in the weeks after the shooting.

“In Iraq you have structure,” Donohue said. “You know what time you’re waking up, you know what time your chow is.”

Now he’s back to Iraq status.

He’s up at 4:15 a.m., out the door by 4:40, and at the gym at 5 a.m. By 6:30 a.m. he’s at J.M. Ullom Elementary School.

Donohue has found time in his schedule to keep in touch with friends who were at the concert, and has also heard from colleagues he’s met in the military.

One lieutenant made a sobering comparison.

“He reached out to me, wanted to make sure I was alright,” Donohue said. “He said, ‘Man, you leave here, and you were safer here in Iraq that you were in your hometown.’ ”

“You might be right,” Donohue replied.

In nine months in Iraq, he recalls taking incoming fire, “here and there.”

“They were very few and far between, as opposed to however many rounds were shot at us that night,” he said. “It’s (in)comparable.”

Donohue admits he’s not sure what made him react the way he did that night.

It could be his military training. It could just be him being himself.

Or it might be a little bit of both.

“The way the military and the army raised us is you never leave a fallen soldier behind,” Donohue said. “You never leave a comrade behind. You do what you have to do in order to take care of people.”

Contact Natalie Bruzda at nbruzda@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3897. Follow @NatalieBruzda on Twitter.

Many U.S. veterans sprang into action on the night of Oct. 1 to help others in need. Here are some of their stories:

— Darius Harper, 46, of Las Vegas, joined the U.S. Army on Sept. 27, 1990. He retired as a Sergeant First Class on Dec. 12, 2015. On the night of Oct. 1, he was performing CPR on a woman when he realized she needed to get to the hospital. He ran a quarter mile to pick up his SUV, and upon his return to the venue, she died. He then used his vehicle to take at least five people to the hospital.

— Taylor Winston, 29, of Ocean Beach, California, used a stolen pickup truck to transport victims to the hospital. Winston drove between 10 to 15 shooting victims to Desert Springs Hospital Medical Center in two separate trips. A Phoenix-area used-car dealer gifted Winston with a 2013 F150 truck to thank him for his selflessness.

— Robert Ledbetter, 42, of Las Vegas, is a retired scout sniper from the U.S. Army Rangers, according to the Los Angeles Times. He helped several people, including man who had been shot in the leg by using a flannel shirt to make a tourniquet, the Los Angeles Times reported.

— Marine combat veteran Scott Yarmer, of Aurora, Colorado, and his friend, led people behind the wall of a bar in the middle of the venue, according to KDVR in Denver. There, they waited for the gunman to pause and reload, and then moved again, KDVR reported.

— Jon Tampien, an Army veteran from Spokane, Washington, used tables as shields to protect his wife and their other family members, according to KHQ-TV.